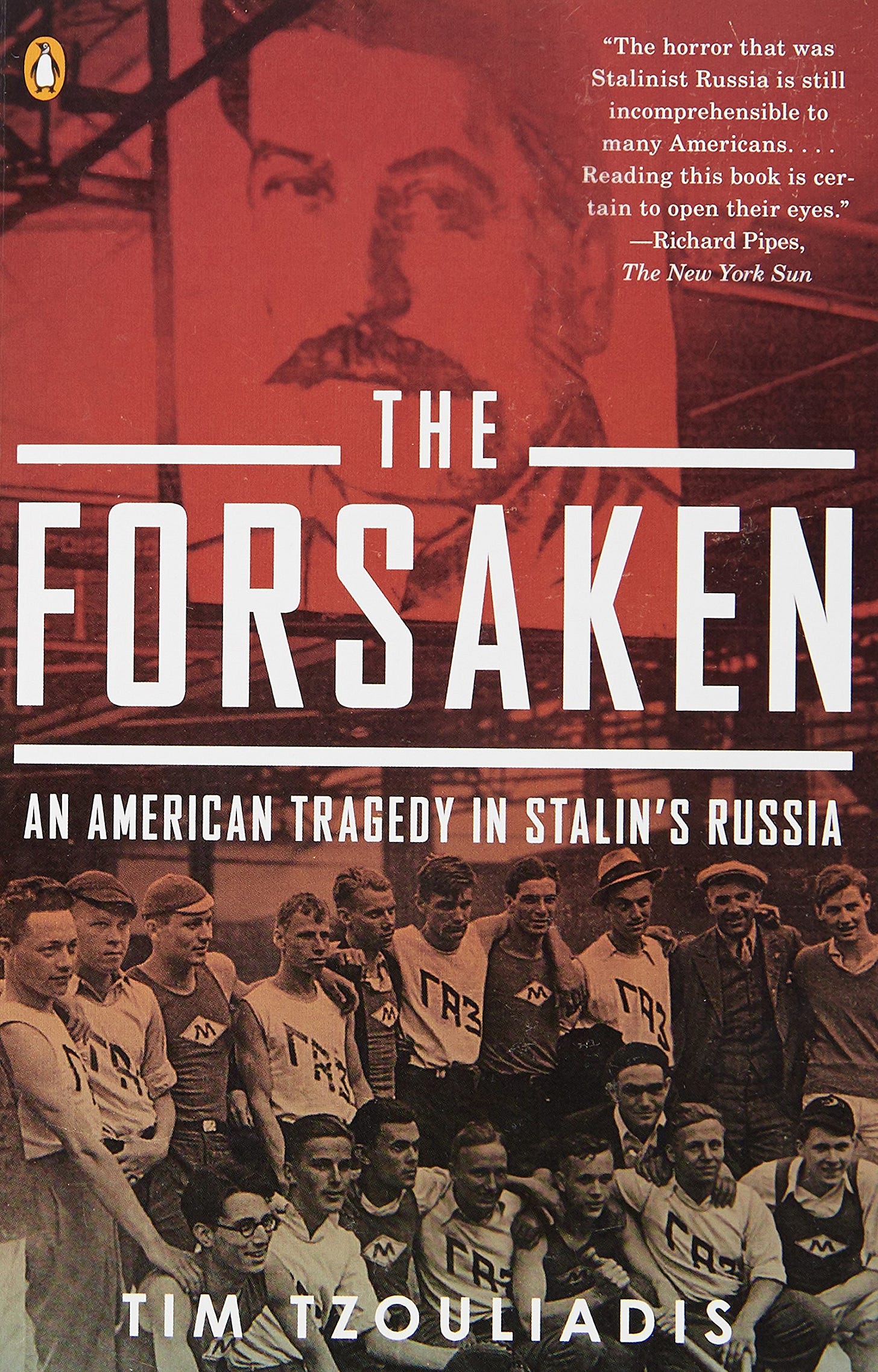

“The Forsaken - An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia” by Tim Tzouliadis

From the back cover:

“A remarkable piece of forgotten history – the never-before-told story of Americans lured to Soviet Russia by the promise of jobs and better lives, only to meet a tragic end.

“The Forsaken begins with the photograph of a baseball team. The year is 1934, and these two rows of young men look like any group of American ballplayers, except perhaps for the Russian lettering on their jerseys. The players have left their homeland and the Great Depression in search of a better life in Stalinist Russia. They will meet tragic, and until now forgotten, fates. Within four years, most of them will be arrested alongside untold numbers of other Americans. Some will be executed immediately. Others will be sent to “corrective labour” camps where they will be starved and worked to death. This book is the story of the forsaken who died and those who survived.”

A text copy can be found here

https://celz.ru/tzouliadis-tim/page,1,248534-the_forsaken_an_american_tragedy_in_stalins_russia.html

Precis:

“Of all the great movements of population to and from the United States, the least heralded is the migration, in the depths of the Depression of the nineteen-thirties, of thousands of men, women and children to Stalin's Russia. […] Communism promised dignity for the working man, racial equality, and honest labour. What in fact awaited them, however, was the most monstrous betrayal.

[…] Through official records, memoirs, newspaper reports and interviews Tim searches the most closely guarded archive in modern history to reconstruct their story – […] idealism brought up against the brutal machinery of repression. His account exposes the self-serving American diplomats who refused their countrymen sanctuary, it analyses international relations and economic causes but also finds space to retrieve individual acts of kindness and self-sacrifice.”

Setting the scene in Chapter 1. “The Joads of Russia”

“On this occasion we can tell from their uniforms that the Foreign Workers’ Club of Moscow is playing against the Autoworkers’ Club from the nearby city of Gorky. But perhaps such details are unimportant, since many of the American baseball players in the photograph will soon be dead. They will not die in an accident, in a train, or in a plane crash. They will be witnesses to, and victims of, the most sustained campaign of state terror in modern history.

The few baseball players who survive will be inordinately lucky. But they will come so close to death and they will endure such terrible circumstances that they too, at times, may wish they had lost their lives with the rest of their team. Only at that moment, as the camera shutter clicks in the warm summer air of Gorky Park, none of the American baseball players has any idea of their likely fate. Their smiles betray not the slightest inkling.”

[So how did there come to be a Foreign Workers’ Club of Moscow and an Autoworkers’ Club from Gorky playing baseball in Moscow? And how and why were these Americans in Russia in 1934? … ]

Chapter 4: “Fordizatsia”

“No other firm in the United States, or even the world, conducted as much business with Joseph Stalin as the Ford Motor Company between 1929 and 1936. For above all men, Henry Ford – “the Sage of Dearborn” – understood very well that the power and the allure of the automobile transcended ideology. The whole of mankind was in love with speed and, in that respect at least, the Bolsheviks were no different.“

[Back up a few sentences - Henry Ford had sold and transplanted an entire automobile factory from Detroit to Russia …]

“Henry Ford had been only too delighted to sell the necessary industrial blueprints and machinery, together with seventy-five thousand “knocked down” Ford Model A’s from the River Rouge plant. It was a deal sweetened by the guarantee of five years of technical assistance and the promise of American labour and know-how.” [Emphasis added]

“The Soviet contract was worth a staggering forty million dollars, and lest we forget, these were 1930s millions paid for in gold at the height of the Depression.”

[How ironic that] “many of the Americans travelled to Russia only to find themselves working in brand new Soviet factories built by the old capitalist titans of American industry.“

[which somehow could not sustain employment for these very same works back in America …]

[So how did they manage to convince these American to travel to Russia? …]

[Comment: as you read this, it lends weight to the ’conspiracy theory’ that the Great Depression was a contrived and controlled demolition of the western economy, just as the GEC of 2008 was and the looming/ongoing Great COVID Reset.]

[At the height of the Depression the mainstream press (and government), orchestrated a propaganda campaign to paint Soviet Russia as a land of hope, opportunity, freedom and fairness. Tzouliadis cites articles from the New York Times in particular.]

Central to this propaganda campaign – remember Ford’s “promise of American labour and know-how” - was the English translation of New Russia's Primer: The Story of the Five-Year Plan

https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/children/texts/ilin/new/

which [picking up Tzouliadis again]

“had become the unlikely publishing phenomenon of 1931, and American bestseller for seven months and one of the highest selling nonfiction titles of the past decade. Its simple explanations, written originally for Russian schoolchildren [it is published under the group section “Children’s Literature Texts”], were read and reread by an American public searching for answers beyond the deadened reach of another decade of “rugged individualism”. In the midst of Depression misery who could not be attracted to the book’s shared vision of future happiness and social progress?”

[How convenient that the Ford automobile factories had already been shipped across to Russia! The vehemently anti-worker and anti-trade union [Ford] had been “paid forty million dollars for the old Model A plant he had only been planning to scrap”! Of course this didn’t deter the hypocritical “workers of the world unite” Soviets under Stalin!]

Incidentally (and even more ironically), Tzouliadis goes on …

”Lenin himself had been a passionate advocate of [the anti-worker] Ford’s methods of mass production, and Ford’s autobiography, “My Life and Work”, had long been a Soviet bestseller, going through four printings by 1925 alone.“

[…]

“The construction of a “Soviet Detroit”, therefore, was deemed essential to the Bolshevik cause.“

“The problem of relations with the Government of the Soviet Union is … a subordinate part of the problem presented by communism as a militant faith determined to produce world revolution and the “liquidation” (that is to say murder) of all non-believers. There is no doubt whatsoever that all orthodox communist parties in all countries, including the United States, believe in mass murder…. The final argument of the believing communist is invariably that all battle, murder and sudden death, all the spies, exiles and firing squads are justified. “

… William C Bullitt – final dispatch to the State Department, dated April 20, 1936.

William C Bullitt to Secretary of State April 20, 1936: 861.01/2120, RG 59, National Archives II, College Park, Maryland.

From Chapter 9 “Spetzrabota” [Special Work]

“Through the course of 1937 and 1938, Americans such as Victor Herman began to disappear, one after another. Many of the arrested were shot not long afterward, often with their fathers, who had brought them to the USSR. After their denunciation, the baseball players from Boston, Arthur Abolin and his younger brother, Carl, were both arrested and executed with their father, James Abolin, in 1938. Their mother died later, in a concentration camp. Only their younger sister, Lucy Abolin—the precocious drama student of the Anglo-American school—was left untouched.[footnote source 30] Other records emerged that revealed how certain victims were forced to testify against their family members in so-called “confrontation interrogations.” In March 1938, a twenty-five-year-old New Yorker named Victor Tyskewicz-Voskov confessed that his mother had been recruited into “espionage in favor of Germany.” Under extreme duress, Tyskewicz-Voskov denounced his mother to his interrogator as a “Trotskyist, inclined antagonistically against the Soviet power.” The NKVD officers then placed his forty-three-year-old mother in the same interrogation room while her son repeated his denunciation in front of her. His mother bravely confessed her own guilt while steadfastly refusing to implicate her son. They were both executed on June 7, 1938.[ footnote source 31]

In the killing fields of Butovo, twenty-seven kilometers south of Moscow, the depressions in the ground later revealed themselves in aerial photography. The mass graves ran for up to half a kilometer at a time. Nor was there anything particularly unique about Butovo. Within the Soviet Union such “zones” were differentiated only by their location. Orders sent from Moscow were applied uniformly throughout the USSR, from the Polish border across one sixth of the surface of the earth to the Pacific Ocean. If the NKVD were instructed that 250,000 people should fill one of the eight mass graves in Byelorussia, then a similar ratio was applied to every other Soviet republic, and every regional district of Russia, too, including the Moscow region itself. At Butovo, exactly the same procedure was followed by the NKVD brigades as elsewhere.[ 32]

In the 1990s, a Russian society for the rehabilitation of Stalin’s victims located within the files of KGB pensioners a “Comrade S.,” the first komendant of an NKVD execution squad who was willing to be interviewed for the historical record. Comrade S. happily discussed his spetzrabota>— the so-called special work—which he had performed with his team of a dozen executioners during the Yezhovchina, the days of Yezhov. Comrade S. remembered how his unit had waited in a stone house on the edge of the killing fields while their prisoners’ files were checked. How they led their victims to the edge of the pit and held the standard-issue Nagan pistol to the back of their heads. How they pulled the trigger and watched the bodies crumple and fall into the hole in the earth. And then how they repeated the process over and again until, like every other Soviet worker, they had met their quota for the night’s work. At the end of their shift, Comrade S. and the dozen members of his squad would retire to their stone headquarters exhausted, to drink the liters of vodka specially allocated for the job at hand. Obviously their masters understood the traumatic effect the spetzrabota had on the minds of the executioners. The vodka salved their consciences as the dawn rose over Moscow, and a new day began for the city’s fear-filled inhabitants.[ 33]

In the mornings at Butovo, the executioners heard the sound of the bulldozers covering over the mass graves, and the fresh graves being hollowed ready for the next night’s work. In their stone house they washed their hands and faces, removing the inevitable back-spray of blood, and doused themselves in cheap eau de cologne, once again provided by their masters, who seemed to have thought of everything and who understood that the smell of death clings to those who administer it. Although they were allocated leather aprons and gloves and hats to protect their uniforms from the spattered gore of blood and skull and brain, the men found it was impossible to stay clean.[ 34]

Judging from the undisturbed recollections of Comrade S., the NKVD guards remained convinced they were not murderers but righteous executioners sanctioned by their state. With prolonged ideological training, their moral sense became disguised and distorted by euphemism. The brigade was enforcing the “supreme penalty for social defence,” or administering the “nine-gram ration.” Words such as liquidation or repression inadequately concealed the simple act of murder. While numbed by the repetitiveness of their “special work,” the executioners became as passionless as slaughtermen, too busy for introspection. Their spetzrabota did not end for many years; it kept arriving until it was hardly special any longer, just monotonous in its routine. [35] There was, however, one unexpected consequence to their lives. Their work made them wealthy. Each NKVD executioner was paid special ruble bonuses for killing people in “the zones,” so much in fact that their increased salaries excited the envy of their NKVD colleagues not selected for this work. And the ruble bonuses mounted up as, night after night, the pits were filled and new ones were dug again the next morning. [36]

In the fields of Butovo, apple trees were planted over the dead. In Depository No. 7, at the Lubyanka, the NKVD entered their names into four hundred bound volumes. Each name was marked with a red pencil and the note “sentence carried out.” From these books, researchers later calculated that 85 percent of the dead were non-communists, ordinary people who mostly came from the Russian peasantry. Given the scale of the genocide, the fate of the Americans was scarcely a matter of significance. The statistical evidence had no regard for the captain of the Moscow Foreign Workers’ baseball team, Arnold Preedin, or his brother, Walter Preedin, from Boston, Massachusetts, who lay buried in an apple orchard twenty-seven kilometers south of Moscow. [37]

Just a few more selected passages …

“ At the State Department offices in Washington, Bullitt’s sudden hostility might well have seemed exaggerated. Unless witnessed personally, the scale of what was taking place in Russia was difficult to comprehend. In June 1936, on his way to the American diplomats’ rented dacha outside Moscow, Elbridge Durbrow watched a train of fifty cars “loaded down with prisoners, men, women and children together, coming out of Moscow.”[36] No one knew who these people were or their destination, but the prison trains had been seen in operation for several years now by American witnesses from all over Russia. Some, such as the young American writer Ellery Walter, sensed their significance straightaway and took the trouble to report them: “I counted 13 trains, each with 2000 men and women and children bound for Siberia.”[37] Others, such as the American engineer Bredo Berghoff, had chanced upon a prison train while searching for his trunk along a railroad yard. Through the narrow, steel-barred windows, Berghoff could see young men whose eyes stared back at him from the darkness.[38]

Packed with several thousand human beings, each train was destined to travel hundreds, and often thousands, of stifling kilometers to its hidden end point. The system of repression was kept secret, but it had grown so vast that there were continual gaps in the fabric of its concealment. The American witnesses had seen the suffering of those trapped within the carriages, and in an exchange of looks, their fearful eyes carried their own message.

In New York, Davies made no mention of the reports of the disappearances of Americans in Russia, or the trainloads of prisoners seen by his embassy officers pulling out of Moscow, or even the frantic telephone calls received after the callers’ friends had been arrested.[45] Most tellingly, he kept absolutely silent regarding the sounds that had kept his wife awake in their bedroom in Spaso House. Only years later, after their divorce, did Marjorie Merriweather Post reveal how she had listened to the NKVD vans pulling up outside the apartment houses that surrounded the Spaso House gardens. In the middle of the night, she had lain awake listening to the screams of families and children as the victims were taken away by the secret police. It had continued night after night. Like many other historical witnesses of the Terror, Marjorie Davies was also regularly awoken by the intermittent sound of gunfire. Once, when the noise of the guns interrupted her sleep, she turned to Joseph Davies to tell him, “I know perfectly well they are executing a lot of those people.” To which the American ambassador had replied soothingly, “Oh no, I think it’s blasting in the new part of the subway.”[46]

ON THE NIGHT of June 24, 1938, Thomas Sgovio left Moscow sealed into the carriage of a prison train with roughly seventy other prisoners. They formed one unit of a transportation of prisoners, packed tight onto the train for their long journey east. These NKVD prison trains had been specially modified with steel spikes under the carriages to prevent escape, and machine-gun emplacements on the roofs. The number of cars on each train ranged from 60 to 120, allowing several thousand prisoners to be moved at a time to destinations across the Soviet Union’s vast Gulag system. The prison trains moved slowly, in part because of the number of cars on the line but also because the drivers rightly feared the consequence of an accidental derailment. And the slow progress was regularly interrupted by guards, who hammered with wooden mallets on the walls, ceilings, and floors of the train to check that the prisoners were not attempting an escape.[22]

None of the prisoners knew their final destination, although there was an expectation that the farther they traveled the worse it would be—and to a certain extent this was true. But the measure was only relative, not absolute. While Victor Herman’s journey ended in the forest wilderness of central Russia, Thomas Sgovio was transported across the entire length of the USSR to the very end of the line. His ten-thousand-kilometer journey locked in the carriage lasted twenty-eight days, and every stop along the way was marked by the burial of prisoners who had died on board the train. This, too, was completely normal.[23]

A month after his train’s departure, Thomas arrived starved and traumatized at a vast transit camp near Vladivostok, on Russia’s Pacific coast. His transportation was still not over. Here the prisoners waited within a barbed-wire enclosure, inside a vast city of eighty thousand souls, ready for the next stage of their descent.[24] It was the place from which the poet Osip Mandelstam managed to send his last letter, in December 1938, the month of his death: “My health is very poor. I am emaciated in the extreme, I’ve become very thin, almost unrecognisable, but send clothes, food and money—though I don’t know if there’s any point. Try nevertheless, I get terribly cold without any [warm] things . . . This is a transit camp. They didn’t take me to Kolyma. I may have to winter here.”[25]

All prisoners would experience the same shock of the vertiginous fall into the abyss, and at every moment, when they believed they had reached the final depths, they would fall again, lower and lower, until they scarcely recognized themselves as human beings at all. Only then—when they had lost all self-awareness and respect, when they existed only in the most savage primal sense as men stripped bare of all humanity—only then would they have arrived at the very heart of the Gulag. And in this state of starving desperation, they would scarcely recognize their loss. They would be dismissive of even the notion of freedom—like Kant’s dove, which feels the weight of the air on its wings and thinks that it can fly better in the void.

In Kolyma, the coldest temperatures on earth had been recorded at below minus sixty degrees centigrade.36 Officially a rule existed in the camps that the prisoners’ work was canceled if the temperature fell to minus fifty degrees. But the rule was never enforced, and the prisoners never saw a thermometer. Instead, they judged the temperature by other means: at minus forty, the human body made a clinking sound as it exhaled; at minus fifty-five degrees, the man in front disappeared as the air froze into an impenetrable fog; below minus sixty degrees, spit froze in midair.37 In Kolyma, nature was said to be “in league with the executioner,” the extreme cold accelerating the destruction of its victims. Alexander Solzhenitysn would later describe the region as the “pole of cold and cruelty” of the Gulag Archipelago. And, like the train timetables of Auschwitz, the logbooks of Andrei Sakharov’s “death ships of the Okhotsk Sea” would reveal the scale of the tragedy that took place in this one unknown corner of the Soviet Union.38 In complete secrecy, the NKVD fleet had been silently ferrying its human cargo since 1932, and the ships would continue their operations for the next two decades. During this period, millions of prisoners would disembark onto Kolyma’s rocky shore, the majority never to return.

Inevitably, the NKVD followed in the Red Army’s wake to clear the population of all “enemies of the people.” In this process, approximately 1.7 million Poles were arrested and transported east into the Soviet camps.20 The Polish families were separated, the men from the women and children, although the NKVD did not inform them at the outset, in order to avoid needless hysteria and consequent delay. Rather, they were told to pack their toiletries separately, since they would be led to separate places for a sanitary inspection.21 The Poles were then pressed and shut into crowded cattle cars, to be tormented by thirst and cold during the long journey to the terminal points of the Gulag. At Kotlas, in the northern Russian province of Archangel, the trains traveled slowly for ten days across a landscape of barbed wire and watchtowers. A Polish survivor recounted how twelve railroad tracks conjoined at the end of the line, each one occupied by a prison train disgorging thousands upon thousands of frail human beings, their faces blue with cold, shivering in temperatures well below freezing. This mass of humanity was then divided by the tall figures of the NKVD officers wearing long coats, black leather boots, and guns.[22]

___________________________________________________________________________

On August 4, 1937, Popashenko, the NKVD chief of the Kuibyshev region, issued a detailed set of instructions to one of his underlings, a Captain Korobitsin, on how to proceed with the executions:

1. Adapt immediately an area in a building of the NKVD, preferably in the cellar, suitable as a special cell for carrying out death sentences . . .

[…]

3. The death sentences are to be carried out at night. Before the sentences are executed the exact identity of the prisoner is to be established by checking carefully his questionnaire with the troika verdict.

4. After the executions the bodies are to be laid in a pit dug beforehand, then carefully buried and the pit is to be camouflaged.

5. Documents on the execution of the death sentences consist of a written form which is to be completed and signed for each prisoner in one copy only and sent in a separate package to the UNKVD [local administration of the secret police] for the attention of the 8th UGB Department [Registrations] UNKVD.

6. It is your personal responsibility to ensure that there is complete secrecy concerning time, place and method of execution.

7. Immediately on receipt of this order you are to present a list of NKVD staff permitted to participate in executions. Red Army soldiers or militsionery are not to be employed. All persons involved in the work of transporting the bodies and excavating or filling in the pits have to sign a document certifying they are sworn to secrecy.28

Source Footnote 28:

28 Iu. M. Zolotov (ed.), Kniga pamiati zhertv politcheskikh repressi (Ul’ianovsk, Russia: 1996), 797-98; quoted in Barry McLoughin, “Mass Operations of the NKVD, 1937-38: A Survey,” from McLoughlin and McDermott (eds.), Stalin’s Terror, 129.

Difficult reading :-( Knew none of this.

Thank you.